Once visitors arrive at Big Major Cay, they can disembark and interact with the pigs in the warm water or on the island’s white-sand beach.

The juxtaposition of pigs and paradise makes for epic and hard-to-believe photographs and selfies. As a result, the oinkers collectively have established themselves as a social media sensation, achieving Kardashian-style fame practically overnight.

Visitors come from all over the world, just to see and swim with the pigs. The porkers have become official ambassadors of Bahamas tourism.

A book about them, “Pigs of Paradise,”will hit shelves later this month.

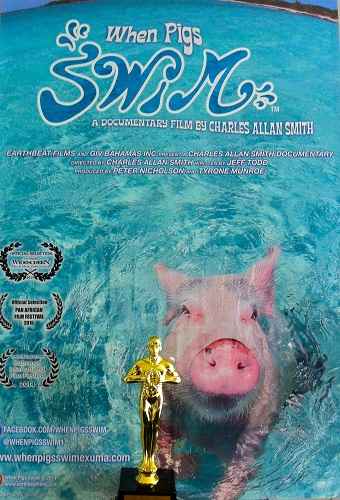

There’s even a full-length documentary film expected by the end of the year.

“These animals certainly have captivated people’s imagination,” says author T.R. Todd. “Swimming with pigs on a beautiful beach is not something you do every day.”

Start of a porcine era

There are many theories about how the pigs first got to Big Major Cay. Some cite shipwrecks or say a storm washed them ashore. Others believe pirates hid them there. As Todd explains in his book, most of these origin stories are folklore.

The real story: Residents of neighboring islands put them there on purpose.

The Exumas are a bit of a playground for the rich and famous. Celebs such as Johnny Depp, Faith Hill and Tim McGraw, and David Copperfield own islands there. As the islands became popular among the Hollywood set in the 1980s and 1990s, locals who had their pigs in pens at home decided to relocate the smelly and often messy animals to a more secluded spot.

Big Major Cay provided the perfect cover. It was far enough away that visitors wouldn’t see or smell the pigs, yet close enough that locals could get the pigs if they needed them.

David Hocher, owner of the Staniel Cay Yacht Club on neighboring Staniel Cay, says Big Major has another critical resource: fresh water.

“Not every island around here has fresh water like Big Major,” says Hocher, who grew up on Staniel Cay. “That island is perfectly set up to support and sustain life.”

A population grows

At first, there were only a handful of pigs on Big Major. Over time the population grew.

Up until as recently as the 1990s, locals would use Big Major as a farm, harvesting animals and slaughtering them as needs arose. In recent years, however, the subsistence aspect has disappeared, though no laws formally protect the pigs from harm.

Today, though numbers ebb and flow, there are about 30 to 40 animals on the island at any given time. Baby pigs roam freely with juveniles, adults and elderly swine. The animals differ in color. Some are all black, while others are mottled black, pink and white. They also have different personalities. Some are eager to interact with people, while others are shy.

Most of the pigs have names. Some, such as Cinnamon and Ginger, were named for their color patterns. Others, such as Raleigh, Roosevelt and Shirley, were named after friends and ancestors. The three large mother pigs were named after matriarchs from Staniel Cay: Blanche, Maggie and Diane.

Bernadette Chamberlain, a local, notes that Mama Diane’s name was changed recently to Mama Karma, because the pig likes to bite visitors in the butt.

“She’s the one you have to look out for,” says Chamberlain. “Don’t ever turn your back!”

Caring for piggies

If anybody around Exuma knows about the pigs, it’s Chamberlain. Earlier this year, she and other volunteers formed the Official Swimming Pigs Association, a nonprofit devoted to caring for the pigs.

The group makes sure the pigs always have fresh water, which they store in three 150-gallon drums at the center of the island. Volunteers also built separate pens for piglets and animals who are ill and need medical treatment. A veterinarian from Nassau provides those services.

Perhaps the most important job for volunteers is to monitor the pigs’ diet.

They do this by mixing vitamins with the water and providing the animals with food pellets to supplement the berries and other items the pigs forage on their own.

Of course, the pigs also eat what visitors feed them. This is why they bum-rush the water when they hear boats. For years, this process went unchecked and tourists would give the pigs everything from lettuce and lobster tails to raw meat and beer.

After a handful of pigs died in early 2017, volunteers made signs designed to raise awareness about the pigs’ health. The signs remind visitors that the “pigs are not garbage disposals,” and that it’s best to feed the animals in the water so they don’t ingest sand.

Stars are born

More than anything else, social media has changed the lives of the swimming pigs. The man behind that effort: Peter Nicholson, partner and director of GIV Bahamas, and majority owner at the Grand Isle Resort & Spa on Great Exuma Cay.

Nicholson, had been aware of the pigs for years and always saw them as a curiosity. In 2013, when he decided to market the Exumas, it hit him: Why not build a campaign around the pigs?

To get the word out, Nicholson hired Todd, a former business editor at the Nassau Guardian. Todd, in turn, hired Charlie Allan Smith, a local filmmaker and video producer. The dynamic duo of Todd and Smith cranked out a

five-minute promotional video spotlighting the pigs.

With the help of the Bahamas Ministry of Tourism, the video went viral, piquing the interest of travel bloggers and celebrities alike. In 2016, the pigs hit the TV circuit, with an appearance on “The Bachelor” and the “Today Show.” The pigs even got their own Instagram page and Twitter account (both @pigsofparadise).

Todd’s book chronicles the pigs’ rise to stardom. It includes colorful history of the islands, thoughtful analysis of the relationship between humans and pigs through time and autobiographical anecdotes about Todd’s other (non-piggie) experiences in the Bahamas. Smith’s feature-length documentary, due out in December, touches on many of these topics as well.

“You’ve got these islands with the most beautiful water in the world, and then you’ve got pigs,” says Smith. “The pairing is just so unexpected. People are drawn to it. It lends itself to a closer look.”

Getting piggy with it

Of course the best way to experience the pigs is to see them in person.

Big Major Cay is accessible only by boat, and most vessels take 20 to 30 people at a time. Many boats leave from Staniel Cay; to get there, visitors first must fly to Nassau, then take a puddle-jumper or boat to the final destination.

Full-day trips also leave from Great Exuma, which is a short plane or boat ride from Nassau as well. Most excursions include a scenic ride, visits with other animals such as Bahamian rock iguanas and stingrays, and a stop at Thunderball Grotto, a sea cave that appeared in the James Bond movie “Thunderball.”

Because the pigs have become so popular, Nicholson and other entrepreneurs have put together subcolonies across the Bahamas. One is closer to the main island of Great Exuma and others in Abaco, Eleuthera/Spanish Wells, Long Island and Nassau.

Wherever you see them, there’s nothing quite like the thrill of observing the piggy-paddle in action, snouts above water in the tropical sun. Once you’ve witnessed this oink-tastic spectacle, every other wildlife experience is just hogwash.